Humanity’s most basic physiological needs consist of air, water, and food. Among these, food holds a special role as an architect of culture. From our hunter-gatherer past, to the industrial revolution, to even the growing movement of organic farming today, our ever-changing ideas and relationship to food has played a fundamental role in defining the epochs of our civilization. Japanese culture in particular has unique relationship to food. Up until the Meiji Restoration, Japan was predominantly a rice-based economy. In other words, capital was synonymous with sustenance. As one of the most well-known and celebrated folk tales in Japan, the story of Momotaro alludes to this deeply enmeshed ontological relationship between food and power distinct to the Japanese psyche. As a folk hero, his strong and upright character captured the minds of many. And with the radical changes that came with modernization, the image of Momotaro evolved with the spirit of times. As Japan joined the imperialist bandwagon at the turn of the 20th century, Momotaro was transformed from a simple folk hero into a national symbol of the empire. As seen in Mitsuyo Seo’s Momotaro’s Sea Eagles, the appropriation of the myth was used to establish and assert Japan’s new place in the global arena, and his militant image saw an increasing departure from the folk hero of the past. Yet with the dissolution of the empire after Japan lost the war, so too the militaristic Momotaro soon vanished. In the 1971 documentary, Minamata: The Victims and their World by Noriaki Tsuchimoto, the symbolic imagery of Momotaro reemerges in the national consciousness in the form of a grass-roots hero. The victims of the Minamata disease equated their pilgrimage throughout the country to Momotaro’s quest to conquer evil. In this sense, Momotaro is able to live a fluid existence, adapting to the psychic needs of the Japanese people through various contexts. In all its manifestations, the myth provides a framework to challenge and negotiate power, as well as deliver a catalyst for community-building through food. If we are to consider myths as public dreams, we can see Momotaro as the Japanese embodiment of the unconscious and universal drive for empowerment. And he carries with him the boon, the humble yet satisfying millet dumpling, which perhaps symbolizes “life force” itself.

As with most folktales, the origins of Momotaro are uncertain. In the standard version of today, the tale of Momotaro begins with an old lady’s encounter with a giant peach drifting down a river. She takes the peach home and presents it to her husband, and in their attempt to cut the peach–lo and behold–out comes a little baby boy. The rejoiced couple names the boy Momotaro, and raises him as their own. Years pass, and Momotaro grows up to be strong and righteous. One day, he resolves to embark on a journey to defeat a gang of ogres in a far away island. His parents, though reluctant at first, concede to his wish, and sends him off with some homemade millet dumplings. On his journey, Momotaro wins the loyalty of a dog, a monkey, and a pheasant; to each he gives a millet dumpling in exchange for their alliance. When they reach Onigashima, the island of ogres, they swiftly defeat the ogres, and the story ends on a triumphant note. Even in this most basic, stripped down synopsis, food plays an explicit role. Moreover, the offering of food appear to symbolize a significant transmission of power and spirit. The dumplings that the old couple prepare for Momotaro’s journey are an embodiment of all that they have to give. And when Momotaro gives each animal a millet dumpling, the transaction binds and unites them. Through the exchange of food, power is negotiable. The social contract between Momotaro and the animals could not happen without mutual agreement of the terms. The fact that the animals are willing to risk their lives in exchange for a millet dumpling suggests the value placed onto food in the story and perhaps even in a broader cultural sense. Survival necessitates sustenance, and thus food becomes the ultimate binder of people.

The countless iterations of Momotaro greatly differ in emphasis, tone, and detail. For example, in the highly condensed 1951 Osaka Koyosha Shuppan version, the encounters between Momotaro and the animals are simple and straightforward. The narrator states, “Momotaro shared his millet dumplings with a monkey, a dog, and a pheasant. They went along with him to Momotaro to serve him and help him.” Similarly, the 1885 version by Hasegawa Takejiro maintains a relatively neutral tone in the encounters between Momotaro and the animals. In comparison, the 1894 version by Iwaya Sazanami exhibits a much more aggressive tone in both Momotaro and the animals. When Momotaro first encounters the dog, the prideful dog threatens to bite his head off. In response, Momotaro says, “You wild dog of the woods, what are you talking about! I am traveling for the sake of the country and am on my way to conquer “Ogres’ Island.” My name is Peach-Boy. If you try to hinder me in anyway, there will be no mercy for you; I, myself, will cut you in half from your head downwards!”. Immediately, the dog retracts his hostility and swears his loyalty to Momotaro. And when the dog politely asks for a millet dumpling, Momotaro gives him only half, reasoning that they are the best millet dumplings in Japan. The dog accepts the half-dumping earnestly, and they continue on their journey. Their encounters with the monkey and the pheasant thereafter continue to display aggression and hostility (particularly between the animals), until each one is tamed by Momotaro’s authoritative command, though they ultimately become friends. It is curious that the first two versions mentioned–written over half a century apart–maintain a similar neutrality in tone, while the Sazanami version is charged with an overtly militant one. It is also strange that Momotaro gives each of the animals only half of a dumpling, for this detail is unique to Sazanami’s version. Overall, the animals have less negotiating power in this version, which may be indicative of the increasingly oppressive power structures during the time it was written. In addition, in this version Momotaro is associated with the divine. Upon his birth, Momotaro tells his parents, “The truth is, I have been sent down to you by the command of the god of Heaven.” The reference to a heavenly mandate is highly reminiscent of the kind of apotheosis that the emperor achieved during the Meiji era. These factor suggest that Momotaro in this incarnation is an allegory for the growing Japanese empire. 1894 is a notable year for Imperial Japan, for it was the year the First Sino-Japanese War was waged, thus marking the Japan’s debut as a world class military power. Perhaps Sazanami, as an eminent figure in children’s literature at the time, felt it was fitting to calibrate the folktale with the national ‘zeitgeist’. And indeed he would not be the last one to do so.

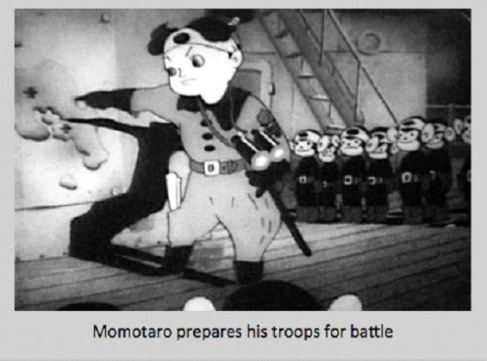

In Momotaro’s Sea Eagles, a 1943 animated film directed by Mitsuyo Seo, we find a version of Momotaro that is far removed from the tale’s traditional depiction. Here the folk hero has been appropriated to fit the militaristic values of Imperial Japan. Released at the height of the Pacific War, it was used as propaganda to inspire patriotism in the Japanese youth. The traditional structure of the folktale is replaced by a narrative embedded in the realism of modern warfare. The film is set on a ship in the open ocean, with a Japanese fleet of animals (including dogs, monkeys, pheasants and rabbits) preparing for an attack of Demon Island: the allegorical Pearl Harbor. Although Momotaro is the commanding officer of the ship, his presence in the film is limited and somewhat detached. This might be surprising considering that the title of the film denotes that the adventure is his, but instead the plot focuses on the actions of the animals. The animals are depicted as comical, endearing, and their playfulness implies the sense of youth. In comparison, the American antagonists are collectively depicted as Bluto, a character from Popeye. The animals’ aerial attack of the Americans can be compared to Momotaro’s attack of Onigashima. Interestingly enough, the film does not depict the Americans as evil, as the Momotaro folktale depicts the ogres. Instead, the Americans are portrayed as lacking basic integrity. The many bottles of alcohol littered on their ship deck suggests a sloppiness. And the commanding officer is a disheveled, blundering drunk who exhibits very little honor or dignity in the face of calamity. In comparison, Momotaro’s dignified presence reinforces the superior character on the Japanese. The triumph of the Japanese cartoon animals over the American Blutos is certainly allegorical of a broader cultural victory of the Japanese empire over the West.

Thus, in this incarnation of the tale, the negotiation of power is happening on an international scale. Meanwhile, the unequal power relations between Momotaro and the animals seem to be taken for granted. For example, Momotaro is the only human on the ship. The distinction between man vs. animal is one that evokes the image of domesticated animals being dependent on their owners. And the fact that Momotaro is the only character with that speaks throughout the film suggests the lack of power the animals actually have. It would also be wise to mention the minimal role that food plays in this version of Momotaro. Unlike the other incarnations of the story, there is no exchange of the millet dumplings between Momotaro and the animals. While there are scenes that do feature millet dumplings, it doesn’t seem to have the same weight that the dumplings normally have in the plot development. In the various versions of the Momotaro tale, the exchange of food for service is crucial to the bond created between Momotaro and the animals. Without it, power relations between Momotaro and the animals become opaque and abstracted. But considering the intended audience of the film, it makes sense that the focus is on the camaraderie between the animals, for it fosters national pride, a fairly new concept at the time. Ultimately, this film delivers a truly modern take on Momotaro as being the symbol of the Japanese national character by re-contextualizing the hero altogether.

With the advent of industrialization, we having become increasingly alienated from our food sources. Thus in our capitalist world, power has become vastly abstracted. The problems that come with such abstraction of power may not be so obvious on a daily basis, but becomes evident in certain circumstances such as when our food security become jeopardized due to entities more powerful than us. An example of this illustrated in Minamata: The Victims and their World, a documentary film made in 1971 by Noriaki Tsuchimoto. The film is about the rural communities in Minamata, Japan affected by a debilitating disease caused by acute mercury poisoning. The disease was caused by mercury being released into the ocean by a factory owned by Chisso Corporation, and gradually reached epidemic proportions. The coastal fishing communities were affected the most, for their main food source was directly being poisoned.

The Minamata disease became an embodiment of a large corporate entity’s oppression of rural, marginalized communities. During their country-wide pilgrimage to publicize their plight and protest the corporation at fault, the members equated their journey to that of Momotaro. Even though victory would not be as clear-cut for the Minamata people as it was for Momotaro, their quest was in the same grass-roots spirit. In a way, the function of food in the documentary is inverted from that of the folktale. In the folktale, the goodness of the food is the uniting force. But for the people of Minamata, it is the damaged state of their food source that brought the community together. Either way, it is food that ultimately brings the people together. In the Minamata documentary, we find an incarnation of Momotaro that reveals considerable tension between 20th century capitalism and the rural communities that struggle against the grain.

The potency of the Momotaro myth is twofold: first, that it uses food to bring people together, and second, that it uses food to negotiate power relations. The ways in which the myth of Momotaro is reinterpreted throughout Japanese history provides profound insights into a culture where food and power are very much entwined.