Jap 70 – Intertextuality/Intermediality Paper:

Professor McKnight; Discussion 1A

Michelle Embury

11/22/13

Momotarō, one of Japan’s most iconic folklore characters, appears in many textual and medial works around throughout Japanese history. Each rendition of Momotarō conveys the story differently. Perhaps most interesting among these differences is the relationship between Momotarō and the animals. In Sazanami’s and Tsuchimoto’s respective renditions of Momotarō, Momotarō represents a figure who unites all, but the way that he is represented as a leader is unique to each work. In Sazanami’s written rendition of Momotarō, the animals originally have some form of rivalry and tension amongst themselves, but are united by their loyalty to Momotarō and the obedience he demands. Momotarō’s authority and strong sense of bravery are emphasized through his interactions with the animals in the story. However, in Tsuchimoto’s film adaptation, Momotarō’s Sea Eagle, the animals already get along well enough independent of Momotarō. He still acts as a uniting figure as their commander of armed forces, but the film focuses mainly on the soldiers and their story in battle. The role Momotarō takes on in different works of art speaks to his national prestige and reputation.

Sazanami’s interpretation of Momotarō follows Momotarō and the animals he encounters upon his journey to defeat the ogres. Such events project Momotarō’s influential and courageous qualities, establishing him as an influential figure in Japanese youth culture.While on his journey to find the ogres, Momotarō encounters the Lord Spotted Dog. After receiving an unfriendly greeting from the dog, Momotaro “laughs mockingly” (23) and states: “‘I, myself, will cut you in half from your head downwards!’” (24), if the dog wouldn’t let him by. Momotarō’s response to the dog’s threat allows him to demonstrate his authority over the animals. At this point, the dog “suddenly put his tail between his legs” and says that if “[Momotarō] will command [him] to be [his] humble servant, to accompany [him], [he] shall be grateful for [his] fortune” (24). Putting his tail between his legs shows the dog’s deference for Momotarō and suggests that he clearly understands Momotarō’s abilities and powers. Referring to himself as a “humble servant” that would be “grateful” to accompany Momotarō on his quest to defeat the ogres illustrates the dog’s loyalty and respect. Each animal that comes into contact with Momotarō offers his or her complete allegiance – the Lord Spotted Dog; the Monkey, who wants to be Momotarō’s “humble servant” (26); the Pheasant, who “offers [his] formal surrender” (31). The animals see Momotarō as an admirable, commanding figure, bringing justice to the land.

Although the animals pledge an unwavering allegiance to Momotarō in the story, their relationship with each other has a rockier beginning. Momotarō must bring the peace and force cooperation among his comrades. For, “The influence of a great General is a wonderful thing! From that time forward, all three animals were the best of friends and obeyed Peach-Boy’s commands, heart and soul” (32). Momotarō serves as the common link to all animals and enforces support and harmony amongst them all. In Sazanami’s interpretation of Momotarō, Momotarō demonstrates certain qualities of strength and courage to be instilled in the youth of Japan.

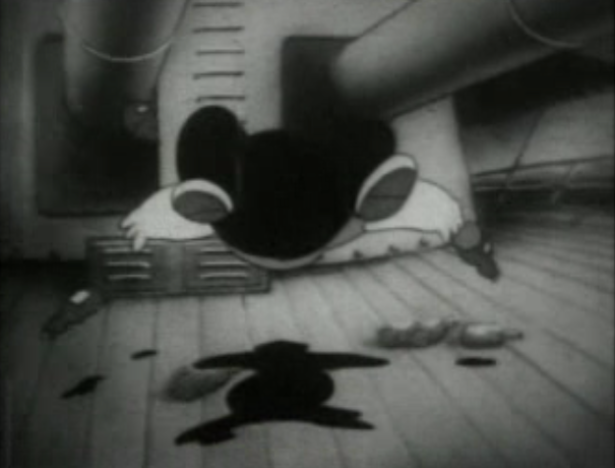

In Tsuchimoto’s film adaptation, Momotarō’s Sea Eagle, Momotarō holds a completely different role – although he still brings solidarity amongst the animals, his role is less present than that in Sazanami’s story. Because this film was created as Japanese propaganda during the WWII period, the attention is geared more toward the soldiers – everyday men – and their experience during war. Momotarō appears in the beginning of the film when the animals are running across deck on the battleship to get in line. At this point Momotarō, surrounded by the different animal groups, communicates that they are to besiege the ogres of Onigashima. Through his provision of information to the animals surrounding him, Momotarō establishes himself as the authoritative figure on the ship. However, as he states: “I your captain, will await your return,” the audience realizes that he will not hold a prominent role throughout the film. Instead, the film will focus on the animal comrades and their fight against the enemies. In fact, Momotarō seems to serve mainly as a national symbol within the film – because Momotarō’s a very renowned folktale character in Japan, he’s a figure with which the audience can easily relate. Seeing a character known for his authority and courage provide strategic information about the attack (location, route, status of the soldiers, etc.), allows to audience to be put at ease because of his reputation outside of the film. However, aside from these informational scenes and some random shots, Momotarō doesn’t make much of an appearance.

The film focuses more on the animals and their relations with each other. Tsuchimoto purposely emphasizes the relationship between the comrades to inspire solidarity and support for the soldiers at war. While preparing for battle, the animals tease each other – tickling each other with their tails and laughing at clumsy attempts to put on bandanas – but their interactions are light-hearted and affectionate. As some of the animals board their planes, the soldiers remaining on the ship shake their hands and pray, demonstrating their strong connection and camaraderie. Their support for one another is again illustrated as the rabbits make noise and wave their hats during sendoff of the other animals to battle. The length of this scene endures for a considerable length of time, emphasizing the amount of support and affection amongst the animals. Although the soldiers consist of a variety of animals – dogs, rabbits, and monkeys – their bond is clearly depicted. Because this film was created to instill national pride and unity amongst Japan during WWII, it was important to depict the soldiers in a positive light. Focusing on the happy times and the strong bond between soldiers allows for the audience to create a positive image of their country’s army and actions during wartime.

Throughout Japan’s history, Momotarō has appeared in many different works in literature and media. Each version of the story has a unique take, oftentimes tailored to serve a certain cause. Sazanami’s folktale of Momotarō follows Momotarō as he journeys to defeat the ogres, focusing on his ease in commanding others and displaying powers of a leader. The main purpose of Sazanami’s folktale is to instill esteemed morals and qualities in the youth in Japan. On the other hand, Tsuchimoto’s film adaptation focuses less on Momotarō as it does on the animals. Momotarō serves as a national symbol, but the animals represent the everyday man – something easily relatable to the audiences at home. For this reason, Tsuchimoto’s film adaptation serves as an effective propaganda piece, expressing national pride and solidarity among the country. Momotarō appears in many different Japanese works, each rendition with a unique stance on his character. Momotarō’s versatility in different works speaks to his prominence in Japanese culture. Although folktales were originally intended for children, Momotarō’s presence in Japanese culture demonstrates the large impact that folklore has on society as a whole.